MENU

BN | BND

BN | BND

-

- All Centrifuges

- Benchtop Centrifuges

- Floor-Standing Centrifuges

- Refrigerated Centrifuges

- Microcentrifuges

- Multipurpose Centrifuges

- High-Speed Centrifuges

- Ultracentrifuges

- Concentrator

- High-Speed and Ultracentrifuge Consumables

- Centrifuge Tubes

- Centrifuge Plates

- Device Management Software

- Sample and Information Management

-

- All Pipettes, Dispensers & Automated Liquid Handlers

- Mechanical Pipettes

- Electronic Pipettes

- Multi-Channel Pipettes

- Positive Displacement Pipettes & Dispensers

- Pipette Tips

- Bottle-Top Dispensers

- Pipette Controllers

- Dispenser & Pipette Accessories

- Automated Pipetting

- Automation Consumables

- Automation Accessories

- Liquid Handler & Pipette Services

Sorry, we couldn't find anything on our website containing your search term.

You are about to leave this site.

Please be aware that your current cart is not saved yet and cannot be restored on the new site nor when you come back. If you want to save your cart please login in into your account.

Sorry, we couldn't find anything on our website containing your search term.

How can chaperones improve recombinant protein production in mammalian cultures?

Lab Academy

- Cell Biology

- Cell Culture

- Reproducibility

- Efficiency

- Cell Culture Consumables

- Essay

This article was published first in "Inside Cell Culture" , the monthly newsletter for cell culture professionals. Find more interesting articles about CO2 incubators/ shakers on our page "FAQs and material on CO2 incubators" .

Read more

Challenges of recombinant protein production

Recombinant protein production has revolutionized biotechnology in recent decades – furthering our understanding of health and disease and being used to produce a broad range of therapeutic proteins and vaccines. Across these applications, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells have been one of the most widely used cell lines, offering high rates of protein synthesis, cell viability, and scalability. However, other mammalian cells including human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) have also been widely adopted and are particularly suited to produce more complex proteins and viral vectors [1].

Although mammalian expression systems are well established for recombinant protein production applications, scientists still face yield, stability, and quality challenges. A major factor is the limited capacity for protein folding and post-translational modifications (PTMs) in cell expression systems.

Under high levels of recombinant protein synthesis, cells can struggle to assemble proteins at the required rate. This can be attributed to the insufficient availability of protein folding machinery in the cell, and results in the accumulation of immature, insoluble proteins that form aggregates. Not only does protein aggregation limit the yields of functional, stable recombinant proteins, but they can have toxic effects on cells, inducing stress responses and cell death [2].

Further adding to this problem, many recombinant proteins are difficult to produce. Complex topological structures, post-translational modifications (PTMs), or the formation of multi-subunit complexes all increase the difficulty of protein assembly. This adds to the likeliness of issues with folding and processing, preventing scientists from attaining high yields and quality.

The use of molecular chaperones in mammalian cell cultures can be a promising strategy to overcome these protein production challenges. In this whitepaper, we explore the benefits that chaperones can have on recombinant protein production, providing insights into the most used chaperones, and how to get the most out of their use.

Although mammalian expression systems are well established for recombinant protein production applications, scientists still face yield, stability, and quality challenges. A major factor is the limited capacity for protein folding and post-translational modifications (PTMs) in cell expression systems.

Under high levels of recombinant protein synthesis, cells can struggle to assemble proteins at the required rate. This can be attributed to the insufficient availability of protein folding machinery in the cell, and results in the accumulation of immature, insoluble proteins that form aggregates. Not only does protein aggregation limit the yields of functional, stable recombinant proteins, but they can have toxic effects on cells, inducing stress responses and cell death [2].

Further adding to this problem, many recombinant proteins are difficult to produce. Complex topological structures, post-translational modifications (PTMs), or the formation of multi-subunit complexes all increase the difficulty of protein assembly. This adds to the likeliness of issues with folding and processing, preventing scientists from attaining high yields and quality.

The use of molecular chaperones in mammalian cell cultures can be a promising strategy to overcome these protein production challenges. In this whitepaper, we explore the benefits that chaperones can have on recombinant protein production, providing insights into the most used chaperones, and how to get the most out of their use.

Read more

What are chaperones?

Chaperones assist with the conformational folding of proteins, transiently binding to and stabilizing folding intermediates. They are essential for protein assembly, helping newly synthesized proteins achieve their correct three-dimensional structure, and preventing aggregation during protein synthesis and maturation.

Increasing chaperone availability in cell cultures can therefore enhance rates of protein assembly, increasing the production of mature, stable proteins. Chaperones also improve protein stability, preventing aggregation, and avoiding the induction of cell stress responses. This way, chaperones can extend cell viability, increasing the amount of protein produced over time.

Chaperones can be broadly split into two major categories: molecular (expressed proteins) and chemical (synthetic or naturally occurring small molecules). Depending on the type of chaperone, different strategies are used for their introduction into cell cultures. For molecular chaperones, expression vectors containing the protein coding sequence can be transfected into cultured cells. However, chemical chaperones can simply be added to the cell cultures in their required dosage and timing.

Increasing chaperone availability in cell cultures can therefore enhance rates of protein assembly, increasing the production of mature, stable proteins. Chaperones also improve protein stability, preventing aggregation, and avoiding the induction of cell stress responses. This way, chaperones can extend cell viability, increasing the amount of protein produced over time.

Chaperones can be broadly split into two major categories: molecular (expressed proteins) and chemical (synthetic or naturally occurring small molecules). Depending on the type of chaperone, different strategies are used for their introduction into cell cultures. For molecular chaperones, expression vectors containing the protein coding sequence can be transfected into cultured cells. However, chemical chaperones can simply be added to the cell cultures in their required dosage and timing.

Read more

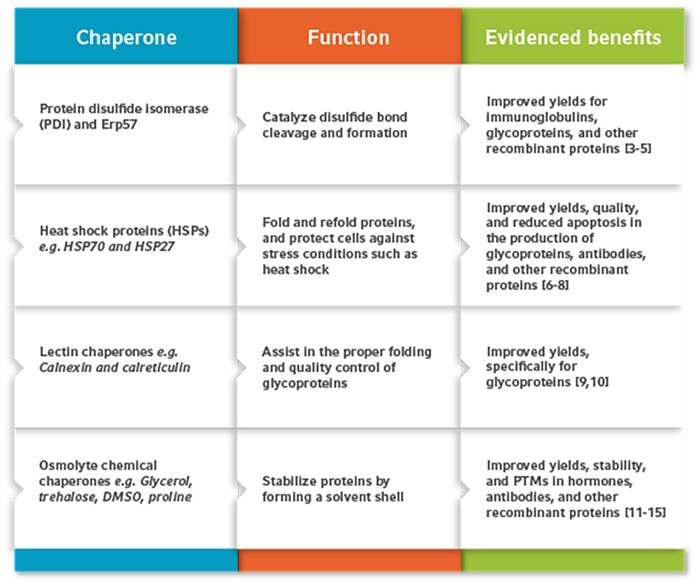

Commonly used chaperones

Protein disulfide isomerase

Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) and its isomer Erp57 are successfully used in recombinant protein production to catalyze disulfide bond cleavage and formation in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). This process is a common bottleneck in recombinant protein production, as disulfide bonds are essential for the correct folding, stability, and biological activity of many mammalian proteins. Increasing the rates of disulfide formation in cell expression systems is particularly beneficial to produce antibodies, which require multiple disulfide bonds linking their light and heavy chains together. The overexpression of PDI or Erp57 in CHO cells has been shown to significantly enhance the folding, quality, and yields of antibodies and other recombinant proteins [3–5].Heat shock proteins

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are also commonly used to enhance recombinant protein production in mammalian cells. Most HSPs are found within the cytoplasm and are upregulated in response to cell stress conditions like high temperature. The HSP family has several functions in the cell, enhancing protein folding, avoiding aggregation, and preventing apoptosis. So far, several HSP subfamilies have successfully enhanced recombinant protein production in mammalian cells. For example, during an experiment in fed-batch CHO cell cultures, the overexpression of HSP70 and HSP27 extended cell viability by 36-72 hr, resulting in a 2.5-fold increase in yields of the recombinant human interferon-γ (IFN-γ) [6]. Transfection with HSP70 on its own has also been effective in mammalian cell lines, including mouse murine myeloma (NS0) cells and baby hamster kidney (BHK)-21 cells, increasing yields and cell culture longevity [7, 8].Lectin chaperones

Some molecular chaperones can be specific to certain types of proteins. This includes lectin chaperones such as calnexin and calreticulin, which assist specifically in glycoprotein folding. These recognize and bind to monoglycosylated oligosaccharides, promoting their correct folding and oligomerization [9]. Calnexin and calreticulin have been used to significantly improve glycoprotein production in mammalian cells. For example, a study in CHO cells showed that the overexpression of these two chaperones resulted in a 1.9-fold increase in the yields of the hormone thrombopoietin [10].Chemical chaperones

A wide range of chemical chaperones have been studied in recombinant protein production. Amongst these, osmolytes are one of the most used types of chemical chaperones. They assist in protein folding and form a solvent shell around protein molecules, stabilizing them and preventing their aggregation. An example of an osmolyte that acts as a chemical chaperone function is glycerol. In CHO cells, the addition of glycerol has been shown to double the yields of the recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) [11]. Glycerol has also been shown to improve post-translational modifications like sialyation in CHO cell cultures [12]. Trehalose is another commonly used chemical chaperone in recombinant protein production. This naturally occurring sugar is found in fungi, bacteria, and invertebrates. When added to CHO cell cultures, trehalose can reduce aggregation by up to two-thirds, as shown in the production of the Ex3-scDb-Fc antibody (Ex3-humanized IgG-like bispecific single-chained diabody with Fc) [13]. Other osmolytes that function as chemical chaperones include dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) and proline, both of which can significantly improve recombinant protein production yields and stability in CHO cell cultures [14, 15].Read more

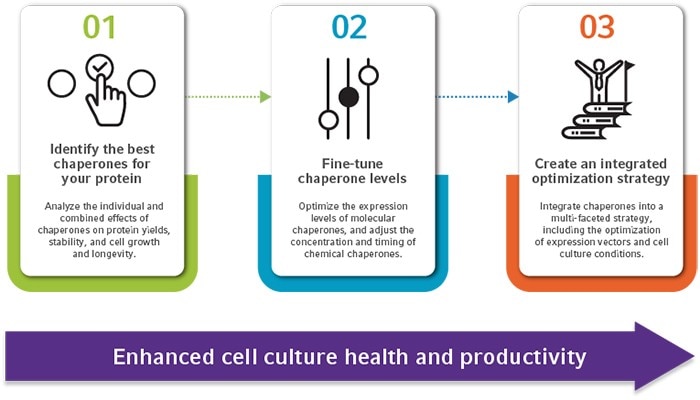

Getting the most out of chaperones

1. Identifying the best-performing chaperones for your cultures

Chaperones can have varied effects on cell culture productivity, and their effect largely depends on the recombinant protein produced. Due to this, the performance of several different molecular and chemical chaperones should be tested for your cell cultures. When analyzing the effects of chaperones, various parameters should be considered, including protein yields, stability, PTMs, and the impact on cell culture growth, health, and longevity. In addition to testing the role of individual chaperones on cell cultures, combinations can be analyzed to maximize cell culture productivity. Several molecular and/or chemical chaperones can be added to the same culture, and the best combination will depend on several factors, including the environmental conditions and the recombinant protein [16, 17].2. Optimizing concentration and timing

Once the best-performing chaperone(s) are identified, the concentrations of these should then be optimized. For molecular chaperones, expression levels of the chaperone relative to the recombinant protein should be analyzed and adjusted [17]. For chemical chaperones, both the concentration and timing should be optimized, as osmolyte chemical chaperones can inhibit cell proliferation in a dose- and time-dependent manner. For this reason, osmolyte chemical chaperones like glycerol and DMSO are often added in low concentrations to cultures after cells have reached their required density [15, 18].3. Integrating other cell culture optimization techniques

To maximize protein production, chaperone addition should be integrated with other optimization strategies. This includes modification of the recombinant protein expression vector, with the need to fine-tune key vector components such as the promoter sequence, codon usage, and fusion tags. This ensures high rates of protein synthesis, which should align with chaperone capacity to avoid protein aggregation and cell stress responses.Read more

Learn more about vector optimization in recombinant protein production

Read more

Environmental conditions also require optimization for maximized protein productio outcomes. This includes cell culture media composition, in addition to cell culture parameters such as temperature, dissolved oxygen, and pH. These factors all largely influence cell health and productivity and can also influence chaperone activity. Therefore, cell culture conditions should be optimized following the addition of chaperones, to ensure optimal yields, quality, and stability.

Read more

Figure 1: A three-step process to using chaperones in recombinant protein production, for optimized cell culture health and productivity.

In summary, the addition of chaperones – both molecular and chemical – can be extremely beneficial for cell cultures. These aid the production of “difficult-to-express” proteins, helping to overcome bottlenecks in protein assembly, and preventing aggregation issues. However, when looking to maximize the production of your recombinant protein, a well-planned, multifaceted strategy is essential. After determining which chaperones are best for your recombinant protein and optimizing their concentration, you should consider how chaperone addition can be integrated into other cell culture optimization strategies, including the adjustment of expression vectors and cell culture conditions.

Read more

References

1. Tan, E., Chin, C. S. H., Lim, Z. F. S., & Ng, S. K. (2021). HEK293 Cell Line as a Platform to Produce Recombinant Proteins and Viral Vectors. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2021.796991

2. Le Fourn, V., Girod, P.-A., Buceta, M., Regamey, A., & Mermod, N. (2014). CHO cell engineering to prevent polypeptide aggregation and improve therapeutic protein secretion. Metabolic Engineering, 21, 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymben.2012.12.003

3. Komatsu, K., Kumon, K., Arita, M., Onitsuka, M., Omasa, T., & Yohda, M. (2020). Effect of the disulfide isomerase PDIa4 on the antibody production of Chinese hamster ovary cells. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 130(6), 637–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2020.08.001

4. Davis, R., Schooley, K., Rasmussen, B., Thomas, J., & Reddy, P. (2000). Effect of PDI Overexpression on Recombinant Protein Secretion in CHO Cells. Biotechnology Progress, 16(5), 736–743. https://doi.org/10.1021/bp000107q

5. Hwang, S. O., Chung, J. Y., & Lee, G. M. (2003). Effect of Doxycycline-Regulated ERp57 Expression on Specific Thrombopoietin Productivity of Recombinant CHO Cells. Biotechnology Progress, 19(1), 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1021/bp025578m

6. Lee, Y. Y., Wong, K. T. K., Tan, J., Toh, P. C., Mao, Y., Brusic, V., & Yap, M. G. S. (2009). Overexpression of heat shock proteins (HSPs) in CHO cells for extended culture viability and improved recombinant protein production. Journal of Biotechnology, 143(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.05.013

7. Ishaque, A., Thrift, J., Murphy, J. E., & Konstantinov, K. (2007). Over-expression of Hsp70 in BHK-21 cells engineered to produce recombinant factor VIII promotes resistance to apoptosis and enhances secretion. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 97(1), 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.21201

8. Lasunskaia, E. B., Fridlianskaia, I. I., Darieva, Z. A., Da Silva, M. S. R., Kanashiro, M. M., & Margulis, B. A. (2003). Transfection of NS0 myeloma fusion partner cells with HSP70 gene results in higher hybridoma yield by improving cellular resistance to apoptosis. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 81(4), 496–504. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.10493

9. Leach, M. R., & Williams, D. B. (2003). Calnexin and Calreticulin, Molecular Chaperones of the Endoplasmic Reticulum, 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-9258-1_6

10. Chung, J. Y., Lim, S. W., Hong, Y. J., Hwang, S. O., & Lee, G. M. (2004). Effect of doxycycline-regulated calnexin and calreticulin expression on specific thrombopoietin productivity of recombinant chinese hamster ovary cells. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 85(5), 539–546. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.10919

11. Rezaei, M., Zarkesh-Esfahani, S. H., & Gharagozloo, M. (2013). The effect of different media composition and temperatures on the production of recombinant human growth hormone by CHO cells. Research in pharmaceutical sciences, 8(3), 211–7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24019831/

12. Rodriguez, J., Spearman, M., Huzel, N., & Butler, M. (2005). Enhanced production of monomeric interferon-beta by CHO cells through the control of culture conditions. Biotechnology progress, 21(1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1021/BP049807B

13. Onitsuka, M., Tatsuzawa, M., Noda, M., & Omasa, T. (2013). Chemical chaperone suppresses the antibody aggregation in CHO cell culture. BMC Proceedings, 7(S6). https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-6561-7-s6-p68

14. Hwang, S., Jeon, C., Cho, S. M., Lee, G. M., & Yoon, S. K. (2011). Effect of chemical chaperone addition on production and aggregation of recombinant flag-tagged COMPangiopoietin 1 in chinese hamster ovary cells. Biotechnology Progress, 27(2), 587–591. https://doi.org/10.1002/btpr.579

15. Liu, C.-H., & Chen, L.-H. (2007). Promotion of recombinant macrophage colony stimulating factor production by dimethyl sulfoxide addition in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 103(1), 45–49. https://doi.org/10.1263/jbb.103.45

16. Jossé, L., Smales, C. M., & Tuite, M. F. (2012). Engineering the Chaperone Network of CHO Cells for Optimal Recombinant Protein Production and Authenticity (pp. 595–608). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-61779-433-9_32

17. Johari, Y. B., Estes, S. D., Alves, C. S., Sinacore, M. S., & James, D. C. (2015). Integrated cell and process engineering for improved transient production of a “difficult-to-express“ fusion protein by CHO cells. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 112(12), 2527–2542. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.25687

18. Liu, C.-H., & Chen, L.-H. (2007). Enhanced recombinant M-CSF production in CHO cells by glycerol addition: model and validation. Cytotechnology, 54(2), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10616-007-9078-z

2. Le Fourn, V., Girod, P.-A., Buceta, M., Regamey, A., & Mermod, N. (2014). CHO cell engineering to prevent polypeptide aggregation and improve therapeutic protein secretion. Metabolic Engineering, 21, 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymben.2012.12.003

3. Komatsu, K., Kumon, K., Arita, M., Onitsuka, M., Omasa, T., & Yohda, M. (2020). Effect of the disulfide isomerase PDIa4 on the antibody production of Chinese hamster ovary cells. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 130(6), 637–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2020.08.001

4. Davis, R., Schooley, K., Rasmussen, B., Thomas, J., & Reddy, P. (2000). Effect of PDI Overexpression on Recombinant Protein Secretion in CHO Cells. Biotechnology Progress, 16(5), 736–743. https://doi.org/10.1021/bp000107q

5. Hwang, S. O., Chung, J. Y., & Lee, G. M. (2003). Effect of Doxycycline-Regulated ERp57 Expression on Specific Thrombopoietin Productivity of Recombinant CHO Cells. Biotechnology Progress, 19(1), 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1021/bp025578m

6. Lee, Y. Y., Wong, K. T. K., Tan, J., Toh, P. C., Mao, Y., Brusic, V., & Yap, M. G. S. (2009). Overexpression of heat shock proteins (HSPs) in CHO cells for extended culture viability and improved recombinant protein production. Journal of Biotechnology, 143(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.05.013

7. Ishaque, A., Thrift, J., Murphy, J. E., & Konstantinov, K. (2007). Over-expression of Hsp70 in BHK-21 cells engineered to produce recombinant factor VIII promotes resistance to apoptosis and enhances secretion. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 97(1), 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.21201

8. Lasunskaia, E. B., Fridlianskaia, I. I., Darieva, Z. A., Da Silva, M. S. R., Kanashiro, M. M., & Margulis, B. A. (2003). Transfection of NS0 myeloma fusion partner cells with HSP70 gene results in higher hybridoma yield by improving cellular resistance to apoptosis. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 81(4), 496–504. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.10493

9. Leach, M. R., & Williams, D. B. (2003). Calnexin and Calreticulin, Molecular Chaperones of the Endoplasmic Reticulum, 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-9258-1_6

10. Chung, J. Y., Lim, S. W., Hong, Y. J., Hwang, S. O., & Lee, G. M. (2004). Effect of doxycycline-regulated calnexin and calreticulin expression on specific thrombopoietin productivity of recombinant chinese hamster ovary cells. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 85(5), 539–546. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.10919

11. Rezaei, M., Zarkesh-Esfahani, S. H., & Gharagozloo, M. (2013). The effect of different media composition and temperatures on the production of recombinant human growth hormone by CHO cells. Research in pharmaceutical sciences, 8(3), 211–7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24019831/

12. Rodriguez, J., Spearman, M., Huzel, N., & Butler, M. (2005). Enhanced production of monomeric interferon-beta by CHO cells through the control of culture conditions. Biotechnology progress, 21(1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1021/BP049807B

13. Onitsuka, M., Tatsuzawa, M., Noda, M., & Omasa, T. (2013). Chemical chaperone suppresses the antibody aggregation in CHO cell culture. BMC Proceedings, 7(S6). https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-6561-7-s6-p68

14. Hwang, S., Jeon, C., Cho, S. M., Lee, G. M., & Yoon, S. K. (2011). Effect of chemical chaperone addition on production and aggregation of recombinant flag-tagged COMPangiopoietin 1 in chinese hamster ovary cells. Biotechnology Progress, 27(2), 587–591. https://doi.org/10.1002/btpr.579

15. Liu, C.-H., & Chen, L.-H. (2007). Promotion of recombinant macrophage colony stimulating factor production by dimethyl sulfoxide addition in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 103(1), 45–49. https://doi.org/10.1263/jbb.103.45

16. Jossé, L., Smales, C. M., & Tuite, M. F. (2012). Engineering the Chaperone Network of CHO Cells for Optimal Recombinant Protein Production and Authenticity (pp. 595–608). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-61779-433-9_32

17. Johari, Y. B., Estes, S. D., Alves, C. S., Sinacore, M. S., & James, D. C. (2015). Integrated cell and process engineering for improved transient production of a “difficult-to-express“ fusion protein by CHO cells. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 112(12), 2527–2542. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.25687

18. Liu, C.-H., & Chen, L.-H. (2007). Enhanced recombinant M-CSF production in CHO cells by glycerol addition: model and validation. Cytotechnology, 54(2), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10616-007-9078-z

Read more